Arms Exports and the Defense Industrial Base

Do arms exports actually bolster the US Defense Industrial Base?

With the resurgence of the Arab-Israeli conflict and Eastern European territory wars, the US has assumed its familiar role of providing arms to allies, partners, and states that share similar national interests. While US arms exports are more common than just these two conflicts, the topic really rises to the forefront during large, dramatic wars. Rhetoric and scholarship alike tend to focus on the implications of national security, ideology, or the billables to the American tax payer. To speak of arms exports as beneficial to the US remains faux pas, likely because of the massive implications of arms proliferation and possible human rights violations by some client states. The National Defense Industry Strategy (NDIS) barely mentions FMS outright. Out of the 60 pages, the topic gets just two paragraphs on page 23 and a brief mention in discussion of Ukraine.1 In a similar vein, the last two Conventional Arms Transfer policies of presidents Biden and Trump spend most of their words discussing national security implications and only a single bullet on ensuring the health of the defense industrial base.2 Is there a gap between the rhetoric and reality of how the arms trade might bolster the defense industry? This paper will evaluate the hypothesis that the US effectively uses the arms trade to bolster its Defense Industrial Base (DIB) in times of lower DoD procurement.

Background

Within the US, the arms industry is both a monopsony and an oligopoly. It is a monopsony because the US Government controls all purchases of arms. Even if other client states are involved, the President of the US (POTUS) or Congress must approve the sale. It is an oligopoly because defense companies are relatively rare. The intensity of the industry, the high barrier of entry and cost of Research and Development (R&D), and issues of confidentiality lead to few suppliers.3 The complexity of arms manufacturing further strengthens the oligopoly, creating long-term contracts for maintenance, parts, or training, that lock in patron-client relationships for long periods.4 In other words, the marginal rate of substitution between weapons from different companies becomes significantly lower after the initial contract is fielded. It is much cheaper to continue repairing, operating, and refurbishing equipment in the same product line rather than switch products along with supply chains, training, etc. With this general structure of the DIB in mind, two major problems should be closely examined: the supply and demand problem and the division of labor problem.

The DIB faces a unique supply and demand problem because of the possibility of war. Like any free market industry, the DIB in peacetime seeks allocative efficiency. That is, defense companies seek to align production with the demands of the consumer (US government in this case) and their own. Companies produce “on demand.”5 In wartime, however, productive efficiency becomes the sole concern, as the survival of the state is at hand. War has the potential to drastically shift the demand curve immediately, but the supply curve will lag significantly behind until defense articles can be produced in greater number. In any other market, this might be unfortunate. In the case of war, it could be existentially catastrophic. The author calls this phenomenon the “wartime supply gap.”

The wartime supply gap reflects the drastic shift in the demand curve (D) between peacetime (D☮) and wartime (DW). The supply curve will not shift as immediately as the US government will require, however. The Δ between the quantity of defense articles available in peacetime (Q☮) and the quantity of defense articles necessary in wartime (QW) is the wartime supply gap. DW is an unknown curve and QW is an unknown variable. Thus, the objective of the US government is to shorten the wartime supply gap as much as possible, without knowing DW or QW.

The second problem to examine is that of division of labor. While not entirely unique to the DIB, the growing complexity of defense articles and weapon systems means that the division of labor can be incredibly extensive. In citing a study conducted on a UK armored personnel carrier, one author noted there were about 200 first-level suppliers, who each used about 18 second-level suppliers, who each used about 7 third-level suppliers, who each used an average of 2-3 fourth-level suppliers.6 That’s about 63,000 nodal linkages from raw material to defense article. Some “second- and third-tier suppliers did not know that they were involved in defence [sic] work.”7 This is a prime example of what F. A. Hayek described as “a problem of the utilization of knowledge not given to anyone in its totality.”8 It stands that increases or decreases in arms production can have wide-spread unforeseen effects on the economy. It further stands that expediting production may induce significant compounded variable costs.

The US has handled the division of labor problem in the DIB in several ways. First, it has encouraged a significant consolidation of the defense industry through corporate mergers and acquisitions from 1980 to 2015. The most significant consolidation came after 1993, when the Secretary of Defense hosted the “Last Supper” to discuss the upcoming lack of defense procurement and the need of more serious defense efforts to save money.9 Second, it has widened the division of labor problem to garner support across several constituencies. Aircraft and ships have parts built in districts across the United States, ensuring that American voters are tied directly to the health of the DIB. To be fair, this mattered more when the DIB had a greater share of the US economy. However, one study proved that increased government spending in a district does indeed lead to more votes.10 This would imply that policymakers have strong incentives to favor more defense manufacturing in their constituencies. If DoD procurement budgets are low, the policymakers may favor the arms trade.

Final approval for arms transfers lies with POTUS, their delegated authorities, and Congress. Each entity has different incentives and disincentives, including campaign financing, votes, international pressure, and national interest. These decisionmakers receive input and feedback from the cabinet, the National Security Council, DoD, and State Department. The United States has several means to achieve arms transfers, which greatly complicates the data available. The most well-known form of transfer is Foreign Military Sales (FMS). In the FMS process, the US reaches an agreement with a client state to sell defense articles. The final sale is approved by POTUS, often delegated to the SECDEF and Secretary of State. Once the sale is agreed upon by patron and client, the DoD puts the order into its acquisitions process, usually meaning it negotiates a contract with the manufacturer.

For more rapid delivery, client states can access a database of Excess Defense Articles (EDA) and pay only for packing, crating, handling, and transportation. Should the client wish for more customization of their order or less DoD involvement, they may opt for Direct Commercial Sales (DCS). Contracts are negotiated directly between the client state and the manufacturer, but all contracts are subject to Presidential approval and congressional review. If the client cannot afford the purchase outright, the US has two options. First, it might offer Foreign Military Financing (FMF), which simply means a loan to the client state for the cost of the transfer. Another option is Building Partner Capacity (BPC), which essentially gifts the defense articles to the client. BPC programs are approved in the same manner as FMS, but must be specifically funded case-by-case.

The arms trade is not the only option for bolstering the DIB during low procurement years, but other methods rarely meet the same scale. For example, from 2008 to 2024, grants, tax cuts, and direct payments to defense companies ranged in summation for $4 Billion - $11 Billion. Compare this to $80.9 Billion in FMS, $157.5 Billion in DCS in FY23 alone. Open-source data on Prepositioned War Reserve Materiel (PWRM) is difficult to find, but these overseas stockpiles are unlikely to solve the wartime supply gap alone. In terms of military and financial value of materiel, arms sales are the strongest alternative for bolstering the DIB when compared to maintaining a large military.

Methodology

This paper will use a positivist research design to evaluate the hypothesis through the use of descriptive statistics. These statistics will drive inductive reasoning in an attempt to find patterns of correlation between focus areas and enable triangulation of results into a conclusion. It is important to note that this paper does not assume intentionality. Whether these results are naturally occurring phenomena or intentional decisions by policymakers is the topic for another paper. Five tests will be triangulated to induce a greater explanation of the relationship between arms transfers and the DIB:

Test #1: The majority of US Arms Exports ought to be built in the US as new equipment, especially in times of low DoD procurement.

Test #2: Decreases in DoD procurement budgets should lead to increases in arms transfer deliveries of newly manufactured equipment.

Test #3: Decreases in DoD procurement budgets should lead to increases in arms transfer orders of newly manufactured equipment.

Test #4: Delivery timeliness of newly manufactured equipment should remain consistent despite decreases in DoD procurement budgets.

Test #5: Industry productivity should remain consistent despite decreases in DoD procurement budgets.

To complete these tests, this paper will use several sources of data. First, it will use historical US budget tables for procurement on defense-related physical capital, published by the White House Office of Management and Budget and adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.11 To assess the delivery, order, and timeliness of arms transfers, it will utilize the transfer register published by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). It will compare arms via the Trend Indicator Value used by SIPRI that represents the transfer of military resources. For tests 2-4, it will filter out any arms transfers of second-hand equipment, or equipment built locally in the client’s territory. Lastly, industry productivity will be measured via the Industrial Production Index (IPI) for Defense and Space equipment, as published by the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED).

Results

Beginning with test #1, figure 2 shows that the majority of US arms exports are most certainly new equipment manufactured by US companies. Throughout most years, over 50% of exports hold true to this category. Interestingly, there seems to be a trailing negative correlation between DoD procurement budgets and the share of exports that are new equipment built in the US. For instance, DoD procurement budgets saw lows in 1975 and 1999, while US-built new equipment saw peaks in 1977 and 2001. Similarly, budgets were high in 1967 and 1986, and US-built new equipment saw lows in 1972 and 1990. The trailing effect seems to be between 2-5 years, which correlates well with the expected delivery times for arms shipments.

This suggests that the US DIB most certainly turns its attention to arms exports when DoD procurement is low. While this does not show the reasoning, one can assume that the US system either incentivizes such actions or dictates them, as the monopsonistic structure of US arms industry would allow for few other explanations.

Moving to Tests 2 and 3, the 1970s are a prime example of each in the affirmative. DoD procurement budgets decreased steadily from 1968 to 1976, and arms transfer orders increased drastically. Referring back to figure 2, most of these orders would be fulfilled by new equipment. As DoD procurement budgets increased in the Reagan administration, orders and deliveries declined steadily. Decreasing budgets in the 1990s and 2010s saw a somewhat different pattern that still saw a net increase in arms transfers, albeit in shorter spurts. The 1990s budget decline seemed to be met with a single spike in arms transfer orders in 1992. The orders were varied among clients, platforms, and other factors. A similar pattern appeared in 2011.

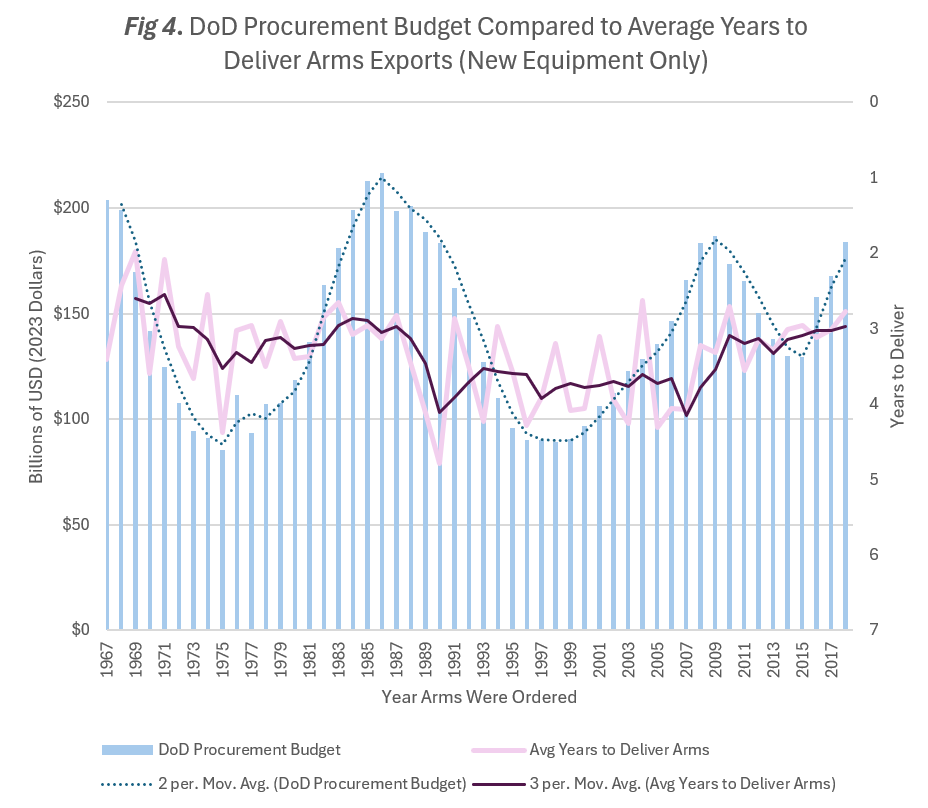

Interestingly, regarding test #4, the DoD procurement budget seems to have no effect on how quickly new arms are delivered to clients. The average delivery times consistently stay between 3 and 4 years. While possibly unintentional, this is still a net positive, as it means that the DIB remains consistent with its client contracts.

More than any other factor, the DIB INDPROD seems to correlate with the DoD procurement budget. 1975 and 1998 show interesting patterns, where it seems as though the index will bottom-out, but seems to be saved by the increase in arms transfers for a short enough time to create a bulge at the bottom of the curve. Outside of these two years, however, the arms trade seems to have little effect on the index when compared to the correlation with DoD procurement budgets.

Conclusion

The results of tests #1-3 suggest that the US does in fact use the arms trade to bolster the DIB when DoD procurement budgets will not. The strong correlations show that when DoD procurement decreases, arms transfers increase. The ability to filter these tests to include just new equipment built by US companies is especially telling to the truth of the results. This level of fidelity enables us to ignore the deliveries of second-hand equipment and focus entirely on the transfers that directly affect the DIB.

Tests #4 and #5 attempt to measure the effectiveness of using the arms trade to bolster the DIB and the results seem less conclusive. They are a testament, however, to the scale of this discussion and in comparing arms sales to DoD procurement. The US military is a truly massive enterprise and the DIB is no exception. The highest level of arms exports found on these charts was in 2011. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s order of 121 F-15s made up nearly half of the total that year. This accounts for about one-third of the Kingdom’s current stock of Fighter / Ground-Attack Aircraft. It follows, then, that a contract to completely overhaul a third of a regional power’s air force will only produce less than 4% of the US stock of the same asset.16 The US is such a massive superpower compared to the other powers of the world that it would need to arm every major power beyond any reasonable level to maintain a constant industrial production index. So long as the US remains the pre-eminent superpower, it is unlikely that it will be able to meet true wartime demand while in peace.

To bring these findings together, it seems clear from the results that the US does, in fact, increase arms sales to bolster the defense industrial base in times of low DoD procurement. Again, this study does not cover intentionality. Yet, when procurement decreases, arms sales increase. However, arms sales alone are not enough to support the DIB completely. The US would essentially need to create another superpower via arms sales to maintain perfectly the level of production in the defense industry any time that DoD procurement dropped.

Department of Defense, National Defense Industrial Strategy, (Department of Defense, 2023), 23, 15, https://www.businessdefense.gov/docs/ndis/2023-NDIS.pdf.

Joseph R. Biden, Jr., “Memorandum on United States Conventional Arms Transfer Policy” (White House, 2023), https://whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2023/02/23/memorandum-on-united-states-conventional-arms-transfer-policy/; Donald J. Trump, “National Security Presidential Memorandum Regarding U.S. Conventional Arms Transfer Policy” (White House, 2018), https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/presidential-actions/national-security-presidential-memorandum-regarding-u-s-conventional-arms-transfer-policy.

Johannes Blum, “Arms production, national defense spending, and arms trade: Examining supply and demand,” European Journal of Political Economy 60 (2019): 2.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Keith Hartley, Economics of Arms, (Agenda Publishing, 2017), 30.

Ibid.

F. A. Hayek, “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” The American Economic Review 35, No. 4. (1945): 520.

Luke A. Nicastro, “The U.S. Defense Industrial Base: Background and Issues for Congress,” CRS report R47751 (Congressional Research Service, 2024), 28-32.

Steven D. Levitt and James M. Snyder, “The Impact of Federal Spending on House Election Outcomes,” NBER Working Paper Series, Working Paper No. 5002, (National Bureau of Economic Research, 1994), 23-24.

“Table 9.4—National Defense Outlays for Major Public Direct Physical Capital Investment: 1940–2025,” White House Office of Management and Budget, accessed November 20th, 2024, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/historical-tables/; adjusted for inflation by using the CPI at “Consumer Price Index, 1913-,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, accessed November 20, 2024, https://www.minneapolisfed.org/about-us/monetary-policy/inflation-calculator.

“Register of transfers of major arms,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, accessed November 20, 2024, https://armstransfers.sipri.org/ArmsTransfer/TransferRegister.

“Table 9.4.”; “Consumer Price Index, 1913-.”; “Register of transfers of major arms.”

Ibid.

“Table 9.4.”; “Consumer Price Index, 1913-.”

International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance 2021, (Routledge, 2021), 29.