Officers are often fired, relieved, or moved out of key positions at every level at the onset of major wars. Even Generals are not immune. This all-too-common feature of wars begs many questions. Did they deserve to be fired? Was firing them a better choice than letting them learn? Or, the focus of this article, if their bosses disagreed with their tactics or wartime decisions, should those disagreements not have come to light in peacetime?

There is an inherent difference in what militaries value between peacetime and war. This difference stems from the subjective measurements of war preparedness. The military officer must prepare their force and their mind for not just for war but a war that has yet to exist. That is to say, a war that currently exists only in their imagination. Predicting the future of warfare can be a dangerous game that often goes wrong. As such, peacetime militaries gravitate towards tangible metrics to judge the war readiness of their units. Nevertheless, failing to look to the future may leave a military behind in terms of technological and tactical advantage. This feature creates a tension between the skills of a successful peacetime commander and a great wartime commander.

In his book On Grand Strategy, John Lewis Gaddis invoked the analogy of the fox (who knows many things) and the hedgehog (who knows one big thing). He argues that it is best to be both. That is, leaders should understand deeply both their potentially infinite aspirations and their limited capabilities. To put it in the context of this article, military commanders must be imaginative in their operational and tactical concepts but remain grounded in the realities that face them from within and outside their force.

The challenges of preparing for the future

Due to the nature of command, the only imagination of future war that matters in peacetime is that of the senior commander. Again, accurate predictions of the future are incredibly difficult. Yet, the commander has a vital role as their subordinates’ mentor, coach, and teacher. They must impart their tactical understandings onto their unit and train their unit for the war they imagine. Disagreements on the adversary and how to employ forces default to the commander, and they might admonish and discourage those who view the future differently. As such, they may create an echo chamber, for better or worse. If the more obstinate subordinates openly question the wisdom of a senior commander, they risk dissension in the ranks and eroding the confidence of troops in the unit’s leadership. Whether or not the subordinate’s idea is superior, this affront to the chain of command degrades the morale of the entire unit.

In extreme cases, an institutional refusal to accept any thought other than the “party line” can force out officers of great talent needed to fight the next war. However, militaries cannot accept just any idea as valuable. That could encourage a disjointed approach full of antiquated or unrealistic tactics designed for failure.

Some metrics transcend this concept, and modern militaries tend to gravitate toward them. Materiel readiness, strategic mobility, and medical and physical readiness of personnel all turn into the mark of a great commander in peacetime. But each of these metrics does better to measure a unit’s managerial prowess than combat ability. This facet might enable the advancement of the best business people rather than the best commanders for combat. Further, even these metrics can be imperfect. Subordinates may “cook the books” to look good or to simply survive in their current position. In such instances, superiors may believe a unit to be in a fine state of combat readiness when they really are in disarray. The lackluster readiness of the Russian Ground Forces serves as a prime example. Seemingly ignorant of the fact, General Valery Gerasimov assured senior leaders that the capabilities of the Russian Military would win the day in the Ukraine offensive. Some analysts claim Russian officers heavily misreported materiel readiness and had been since the Soviet era.

Other metrics like training standards also tend to be highly problematic at higher echelons. They might either be overly prescriptive or too subjective. Finding a balance is difficult. Indeed, individual technical skills and crew-level drills lend themselves to objective qualitative measurement. Gunnery, marksmanship, navigation, radio handling, and driving are all tangible skills that can be run through courses and judged on time and performance. Still, once the task of defeating an adversary enters the metric at any level, imaginations get involved. This challenge is difficult to overcome even with modern simulations or “paints” built into training. One option is to create highly detailed “step-action” checklists, but such a technique removes a commander’s ability to react to a thinking enemy or to think creatively in combat. The disaster of France’s bataille conduit — where highly centralized command and control led to several tactical failures early in the Second World War — should be enough warning to stray away from such methods.

The need for imagination

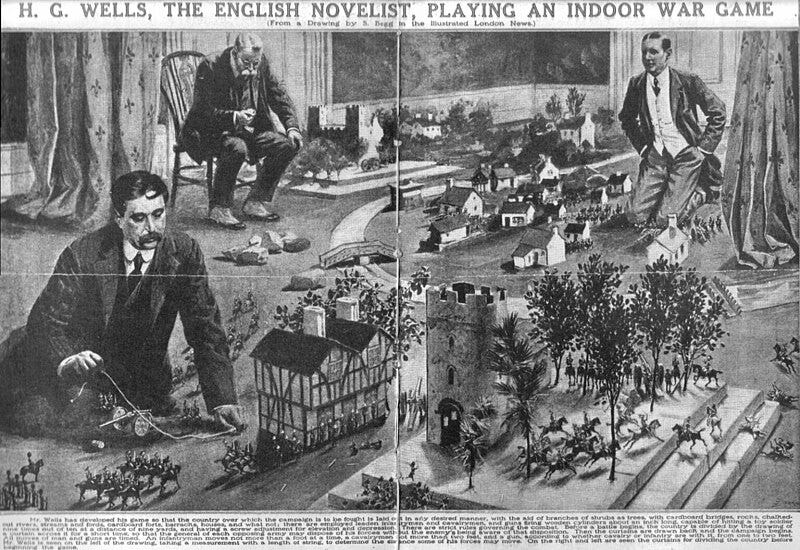

So what are modern militaries to do? How do they build a military ready for the next war? While many other factors are in play, one often overlooked quality in military leaders is that of imagination.

Imagination enables commanders to think about — and therefore prepare for — more than one type of war. Modern commanders must consider the realities of counterinsurgencies and large-scale combat, urban and rural battles, maneuver, firepower, and positional warfare. War takes many forms. Further, the grand majority of predictions about future war are wrong. Partly, this is by nature. One belligerent’s war preparation is another belligerent’s threat, and so we end up with a meeting engagement of ideas, each adapting to the other before the war even starts. Just the same, commanders should wish away their problems and shortfalls in hopes that they will be cared for by the benevolent institution they serve. “In war, it will be different,” I might be thinking too, hopefully. Resources are limited. Militaries must choose carefully where to invest and how to train in peacetime, just as they must in war. So, the realities of resources must temper imaginations.

Imagination allows commanders to think about risks that may not yet be known. Threats today adapt faster than ever. Emerging technologies generate widespread use of electromagnetic attacks and innovative new forms of physical destruction. Capabilities meet countermeasures, which are countered in turn through more innovation. The global arms trade is alive and well, proliferating threats that deny superiority to stronger nations. Imagination, then, must also be tempered by a sense of pessimism.

Imagination can, however, carry commanders away to distant realities. The French bataille conduit, mentioned earlier, made the critical mistake of assuming commanders would have more control over a developing battle than they ever could. Since then, firepower theories have made the same assumption, including the once-defunct US theory of effects-based operations. The idea is an attractive devil. Increasing capabilities to sense and strike targets with real-time command and control incite a natural human tendency of commanders to want immediate feedback. Unfortunately, it remains the adversary’s interest to actively disrupt such feedback, and the fog of war lives on as a fundamental nature of human conflict. As such, a clear understanding of the nature of war in theory and practice must also temper imagination.

***

This trait, of course, is not the end-all-be-all. Yet, it is a highly underappreciated quality in militaries. Armed forces value uniformity, obedience to orders, and routine. These traits are opposites to imagination. So, military professionals must pull imaginative and creative young leaders up in their organization. They should be educated in the realities of war, the risk decisions commanders make, and the nature of war in theory and in practice. This education should encourage their creativity and stoke their tactical imaginations. This is easier said than done, as every force must also learn the basics of their craft. That is the difference between training to tactics and training to techniques or procedures, which will be the topic of a future post.